What Monotheistic Religion Was Introduced to Mesopotamia Around 600 B.c.e.?

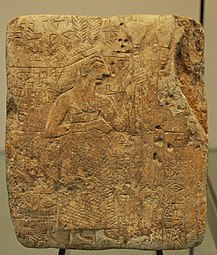

Wall plaque showing libations past devotees and a naked priest, to a seated god and a temple. Ur, 2500 BCE.[1] [2]

Sumerian organized religion was the organized religion skilful past the people of Sumer, the first literate civilisation of aboriginal Mesopotamia. The Sumerians regarded their divinities equally responsible for all matters pertaining to the natural and social orders.[3] : 3–four

Overview [edit]

Before the beginning of kingship in Sumer, the city-states were effectively ruled by theocratic priests and religious officials. Later, this role was supplanted past kings, merely priests continued to exert peachy influence on Sumerian society. In early on times, Sumerian temples were simple, 1-room structures, sometimes built on elevated platforms. Towards the end of Sumerian culture, these temples developed into ziggurats—tall, pyramidal structures with sanctuaries at the tops.

The Sumerians believed that the universe had come up into existence through a series of cosmic births. First, Nammu, the primeval waters, gave nascency to Ki (the world) and An (the sky), who mated together and produced a son named Enlil. Enlil separated heaven from earth and claimed the earth every bit his domain. Humans were believed to accept been created past Enki, the son of Nammu and An. Sky was reserved exclusively for deities and, upon their deaths, all mortals' spirits, regardless of their behavior while alive, were believed to go to Kur, a cold, dark cavern deep beneath the earth, which was ruled past the goddess Ereshkigal and where the merely nutrient available was dry dust. In later times, Ereshkigal was believed to rule alongside her husband Nergal, the god of death.

The major deities in the Sumerian pantheon included An, the god of the heavens, Enlil, the god of wind and storm, Enki, the god of water and human civilization, Ninhursag, the goddess of fertility and the earth, Utu, the god of the sun and justice, and his begetter Nanna, the god of the moon. During the Akkadian Empire, Inanna, the goddess of sex, beauty, and warfare, was widely venerated across Sumer and appeared in many myths, including the famous story of her descent into the Underworld.

Sumerian organized religion heavily influenced the religious beliefs of later on Mesopotamian peoples; elements of it are retained in the mythologies and religions of the Hurrians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and other Middle Eastern culture groups. Scholars of comparative mythology have noticed many parallels between the stories of the ancient Sumerians and those recorded later in the early on parts of the Hebrew Bible.[ commendation needed ]

Worship [edit]

Written cuneiform [edit]

Evolution of the word "Temple" (Sumerian: "É") in cuneiform, from a 2500 BCE relief in Ur, to Assyrian cuneiform circa 600 BCE.[iv]

Sumerian myths were passed downwardly through the oral tradition until the invention of writing (the earliest myth discovered and then far, the Epic of Gilgamesh, is Sumerian[ dubious ] and is written on a series of fractured clay tablets). Early Sumerian cuneiform was used primarily as a record-keeping tool; it was not until the late Early Dynastic period that religious writings beginning became prevalent as temple praise hymns[5] and as a form of "incantation" called the nam-šub (prefix + "to cast").[6] These tablets were too fabricated of stone clay or stone, and they used a pocket-size pick to make the symbols.

Architecture [edit]

In the Sumerian city-states, temple complexes originally were small, elevated ane-room structures. In the early dynastic menses, temples developed raised terraces and multiple rooms. Toward the end of the Sumerian civilisation, ziggurats became the preferred temple construction for Mesopotamian religious centers.[9] Temples served as cultural, religious, and political headquarters until approximately 2500 BC, with the rise of military kings known as Lu-gals ("human" + "big")[6] subsequently which time the political and armed services leadership was often housed in separate "palace" complexes.

Priesthood [edit]

Until the advent of the Lugal ("King"), Sumerian city-states were nether a nearly theocratic authorities controlled by various En or Ensí, who served as the loftier priests of the cults of the city gods. (Their female equivalents were known as Nin.) Priests were responsible for continuing the cultural and religious traditions of their city-state, and were viewed equally mediators between humans and the catholic and terrestrial forces. The priesthood resided full-time in temple complexes, and administered matters of land including the large irrigation processes necessary for the civilization's survival.

Ceremony [edit]

During the Third Dynasty of Ur, the Sumerian city-state of Lagash was said to have had lx-two "lamentation priests" who were accompanied by 180 vocalists and instrumentalists.[10]

Cosmology [edit]

The Sumerians envisioned the universe as a airtight dome surrounded past a primordial saltwater sea.[11] Underneath the terrestrial earth, which formed the base of the dome, existed an underworld and a freshwater body of water called the Abzu. The deity of the dome-shaped firmament was named An; that of the earth was named Ki. First the hugger-mugger world was believed to exist an extension of the goddess Ki, merely afterward developed into the concept of Kur. The primordial saltwater ocean was named Nammu, who became known as Tiamat during and later the Ur III catamenia.

Cosmos story [edit]

Carved effigy with feathers. The king-priest, wearing a net skirt and a hat with leaves or feathers, stands before the door of a temple, symbolized by 2 great maces. The inscription mentions the god Ningirsu. Early Dynastic Period, circa 2700 BCE.[12]

The main source of information about the Sumerian creation myth is the prologue to the epic poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld,[13] : xxx–33 which briefly describes the procedure of creation: originally, in that location was only Nammu, the primeval sea.[13] : 37–twoscore Then, Nammu gave birth to An, the sky, and Ki, the earth.[thirteen] : 37–40 An and Ki mated with each other, causing Ki to give birth to Enlil, the god of wind, pelting, and storm.[xiii] : 37–40 Enlil separated An from Ki and carried off the earth every bit his domain, while An carried off the sky.[xiii] : 37–41

Heaven [edit]

The ancient Mesopotamians regarded the sky as a series of domes (usually three, but sometimes seven) covering the flat globe.[14] : 180 Each dome was made of a different kind of jewel.[14] : 203 The lowest dome of heaven was fabricated of jasper and was the dwelling house of the stars.[15] The middle dome of sky was made of saggilmut stone and was the home of the Igigi.[15] The highest and outermost dome of heaven was made of luludānītu rock and was personified as An, the god of the sky.[xvi] [15] The celestial bodies were equated with specific deities too.[xiv] : 203 The planet Venus was believed to be Inanna, the goddess of love, sexual activity, and war.[17] : 108–109 [fourteen] : 203 The sun was her brother Utu, the god of justice,[14] : 203 and the moon was their father Nanna.[fourteen] : 203 Ordinary mortals could not go to heaven because it was the abode of the gods alone.[xviii] Instead, after a person died, his or her soul went to Kur (subsequently known every bit Irkalla), a night shadowy underworld, located deep below the surface of the earth.[18] [nineteen]

Afterlife [edit]

Devotional scene, with Temple.

The Sumerian afterlife was a dark, dreary cavern located deep beneath the ground,[nineteen] [xx] where inhabitants were believed to keep "a shadowy version of life on globe".[xix] This bleak domain was known as Kur,[17] : 114 and was believed to be ruled by the goddess Ereshkigal.[19] [xiv] : 184 All souls went to the same afterlife,[19] and a person's actions during life had no effect on how the person would be treated in the world to come.[19]

The souls in Kur were believed to eat nothing simply dry dust[17] : 58 and family members of the deceased would ritually cascade libations into the expressionless person's grave through a dirt pipe, thereby allowing the dead to potable.[17] : 58 Nonetheless, there are assumptions according to which treasures in wealthy graves had been intended as offerings for Utu and the Anunnaki, so that the deceased would receive special favors in the underworld.[20] During the Third Dynasty of Ur, it was believed that a person'due south handling in the afterlife depended on how he or she was buried;[17] : 58 those that had been given sumptuous burials would be treated well,[17] : 58 but those who had been given poor burials would fare poorly, and were believed to haunt the living.[17] : 58

The entrance to Kur was believed to be located in the Zagros mountains in the far east.[17] : 114 Information technology had 7 gates, through which a soul needed to pass.[19] The god Neti was the gatekeeper.[14] : 184 [17] : 86 Ereshkigal'southward sukkal, or messenger, was the god Namtar.[17] : 134 [xiv] : 184 Galla were a course of demons that were believed to reside in the underworld;[17] : 85 their primary purpose appears to have been to drag unfortunate mortals back to Kur.[17] : 85 They are frequently referenced in magical texts,[17] : 85–86 and some texts depict them as being seven in number.[17] : 85–86 Several extant poems describe the galla dragging the god Dumuzid into the underworld.[17] : 86 The later on Mesopotamians knew this underworld by its East Semitic proper noun: Irkalla. During the Akkadian Flow, Ereshkigal's office as the ruler of the underworld was assigned to Nergal, the god of death.[nineteen] [14] : 184 The Akkadians attempted to harmonize this dual rulership of the underworld by making Nergal Ereshkigal's hubby.[19]

Pantheon [edit]

Development [edit]

It is mostly agreed that Sumerian civilization began at some point betwixt c. 4500 and 4000 BC, but the earliest historical records just date to effectually 2900 BC.[21] The Sumerians originally practiced a polytheistic religion, with anthropomorphic deities representing catholic and terrestrial forces in their earth.[14] : 178–179 The earliest Sumerian literature of the third millennium BC identifies four primary deities: An, Enlil, Ninhursag, and Enki. These early deities were believed to occasionally behave mischievously towards each other, just were more often than not viewed every bit beingness involved in co-operative artistic ordering.[22]

During the middle of the third millennium BC, Sumerian lodge became more urbanized.[14] : 178–179 Equally a effect of this, Sumerian deities began to lose their original associations with nature and became the patrons of diverse cities.[14] : 179 Each Sumerian city-country had its ain specific patron deity,[14] : 179 who was believed to protect the city and defend its interests.[fourteen] : 179 Lists of large numbers of Sumerian deities take been found. Their order of importance and the relationships between the deities has been examined during the study of cuneiform tablets.[23]

During the tardily 2000s BC, the Sumerians were conquered by the Akkadians.[14] : 179 The Akkadians syncretized their own gods with the Sumerian ones,[14] : 179 causing Sumerian religion to take on a Semitic coloration.[fourteen] : 179 Male deities became dominant[fourteen] : 179 and the gods completely lost their original associations with natural phenomena.[14] : 179–180 People began to view the gods as living in a feudal society with class structure.[fourteen] : 179–181 Powerful deities such as Enki and Inanna became seen as receiving their power from the primary god Enlil.[14] : 179–180

Major deities [edit]

The majority of Sumerian deities belonged to a classification called the Anunna ("[offspring] of An"), whereas seven deities, including Enlil and Inanna, belonged to a group of "underworld judges" known as the Anunnaki ("[offspring] of An" + Ki). During the Third Dynasty of Ur, the Sumerian pantheon was said to include sixty times 60 (3600) deities.[fourteen] : 182

Enlil was the god of air, wind, and tempest.[24] : 108 He was also the primary god of the Sumerian pantheon[24] : 108 [25] : 115–121 and the patron deity of the city of Nippur.[26] : 58 [27] : 231–234 His main consort was Ninlil, the goddess of the south wind,[28] : 106 who was one of the matron deities of Nippur and was believed to reside in the same temple as Enlil.[29] Ninurta was the son of Enlil and Ninlil. He was worshipped every bit the god of war, agriculture, and one of the Sumerian air current gods. He was the patron deity of Girsu and one of the patron deities of Lagash.

Enki was god of freshwater, male fertility, and knowledge.[17] : 75 His most important cult centre was the Eastward-abzu temple in the city of Eridu.[17] : 75 He was the patron and creator of humanity[17] : 75 and the sponsor of homo culture.[17] : 75 His primary espoused was Ninhursag, the Sumerian goddess of the earth.[17] : 140 Ninhursag was worshipped in the cities of Kesh and Adab.[17] : 140

Ancient Akkadian cylinder seal depicting Inanna resting her foot on the back of a lion while Ninshubur stands in front of her paying obeisance, c. 2334-2154 BC.[30] : 92, 193

Inanna was the Sumerian goddess of honey, sexuality, prostitution, and war.[17] : 109 She was the divine personification of the planet Venus, the morn and evening star.[17] : 108–109 Her primary cult center was the Eanna temple in Uruk, which had been originally defended to An.[31] Deified kings may have re-enacted the marriage of Inanna and Dumuzid with priestesses.[17] : 151, 157–158 Accounts of her parentage vary;[17] : 108 in well-nigh myths, she is usually presented every bit the daughter of Nanna and Ningal,[30] : ix–11, 16 but, in other stories, she is the girl of Enki or An forth with an unknown female parent.[17] : 108 The Sumerians had more myths most her than whatever other deity.[30] : xiii, xv [13] : 101 Many of the myths involving her revolve effectually her attempts to usurp command of the other deities' domains.[32]

Utu was god of the sun, whose primary centre of worship was the E-babbar temple in Sippar.[33] Utu was principally regarded every bit a dispenser of justice;[14] : 184 he was believed to protect the righteous and punish the wicked.[14] : 184 Nanna was god of the moon and of wisdom. He was the father of Utu and i of the patron deities of Ur.[34] He may have also been the father of Inanna and Ereshkigal. Ningal was the wife of Nanna,[35] as well equally the mother of Utu, Inanna, and Ereshkigal.

Ereshkigal was the goddess of the Sumerian Underworld, which was known as Kur.[xiv] : 184 She was Inanna's older sister.[36] In later myth, her husband was the god Nergal.[fourteen] : 184 The gatekeeper of the underworld was the god Neti.[xiv] : 184

Nammu was a goddess representing the primeval waters (Engur), who gave birth to An (heaven) and Ki (earth) and the first deities; while she is rarely attested as an object of cult, she probable played a central office in the early cosmogony of Eridu, and in later periods continued to announced in texts related to exorcisms.[37] An was the ancient Sumerian god of the heavens. He was the antecedent of all the other major deities[38] and the original patron deity of Uruk.

Most major gods had a so-called sukkal, a minor deity serving as their vizier, messenger or doorkeeper.[39]

Legacy [edit]

Akkadians [edit]

The Sumerians had an ongoing linguistic and cultural substitution with the Semitic Akkadian peoples in northern Mesopotamia for generations prior to the usurpation of their territories by Sargon of Akkad in 2340 BC. Sumerian mythology and religious practices were rapidly integrated into Akkadian civilization,[forty] presumably blending with the original Akkadian belief systems that have been mostly lost to history. Sumerian deities developed Akkadian counterparts. Some remained almost the same until later Babylonian and Assyrian rule. The Sumerian god An, for case, developed the Akkadian counterpart Anu; the Sumerian god Enki became Ea. The gods Ninurta and Enlil kept their original Sumerian names.[ commendation needed ]

Babylonians [edit]

The Amorite Babylonians gained dominance over southern Mesopotamia by the mid-17th century BC. During the Old Babylonian Period, the Sumerian and Akkadian languages were retained for religious purposes; the majority of Sumerian mythological literature known to historians today comes from the Old Babylonian Menstruum,[5] either in the form of transcribed Sumerian texts (near notably the Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh) or in the form of Sumerian and Akkadian influences within Babylonian mythological literature (most notably the Enûma Eliš). The Sumerian-Akkadian pantheon was altered, most notably with the introduction of a new supreme deity, Marduk. The Sumerian goddess Inanna also developed the counterpart Ishtar during the Old Babylonian Period.

Hurrians [edit]

The Hurrians adopted the Akkadian god Anu into their pantheon sometime no later than 1200 BC. Other Sumerian and Akkadian deities adapted into the Hurrian pantheon include Ayas, the Hurrian counterpart to Ea; Shaushka, the Hurrian counterpart to Ishtar; and the goddess Ninlil,[41] whose mythos had been drastically expanded by the Babylonians.[ commendation needed ]

Parallels [edit]

Some stories recorded in the older parts of the Hebrew Bible conduct potent similarities to the stories in Sumerian mythology. For example, the biblical account of Noah and the Great Overflowing bears a hit resemblance to the Sumerian drench myth, recorded in a Sumerian tablet discovered at Nippur.[42] : 97–101 The Judaic underworld Sheol is very similar in description with the Sumerian Kur, ruled by the goddess Ereshkigal, as well as the Babylonian underworld Irkalla. Sumerian scholar Samuel Noah Kramer has likewise noted similarities between many Sumerian and Akkadian "proverbs" and the later Hebrew proverbs, many of which are featured in the Volume of Proverbs.[43] : 133–135

Genealogy of the Sumerian deities [edit]

See also Listing of Mesopotamian deities.

| An | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninḫursaĝ | Enki born to Namma | Ninkikurga born to Namma | Nisaba born to Uraš | Ḫaya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninsar | Ninlil | Enlil | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninkurra | Ningal maybe daughter of Enlil | Nanna | Nergal maybe son of Enki | Ninurta maybe built-in to Ninḫursaĝ | Baba born to Uraš | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uttu | Inanna perhaps as well the girl of Enki, of Enlil, or of An | Dumuzid peradventure son of Enki | Utu | Ninkigal married Nergal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Meškiaĝĝašer | Lugalbanda | Ninsumun | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enmerkar | Gilgāmeš | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Urnungal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See besides [edit]

- Religions of the ancient Near Due east

- Ancient Semitic faith

- Babylonian religion

- Mes

- Mesopotamian mythology

- Sumerian literature

- Zuism

References [edit]

- ^ For a better image: [1]

- ^ Fine art of the Outset Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus . Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. p. 74. ISBN978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Civilization, and Graphic symbol . The Univ. of Chicago Printing. ISBN0-226-45238-7.

- ^ Budge, East. A. Wallis (Ernst Alfred Wallis) (1922). A guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian antiquities. British Museum. p. 22.

- ^ a b "Sumerian Literature". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2009-06-22 .

- ^ a b "The Sumerian Lexicon" (PDF). John A. Halloran. Retrieved 2009-06-23 .

- ^ Art of the Commencement Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus . Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. 2003. p. 75. ISBN978-i-58839-043-1.

- ^ Found loose in soil at the cemetery Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums past the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 525.

- ^ "Inside a Sumerian Temple". The Neal A. Maxwell Plant for Religious Scholarship at Brigham Young University. Retrieved 2009-06-22 .

- ^ Gelb, L.J. (1975). "Homo Ludens in Early Mesopotamia". Studia Orientalia. 46: 43–76 – via Northward-Holland, American Elsevier.

- ^ "The Empyrean and the H2o Above" (PDF). Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991), 232-233. Retrieved 2010-02-xx .

- ^ "Louvre Museum Official Website". cartelen.louvre.fr.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961), Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the 3rd Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Academy of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN0-8122-1047-half-dozen

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j grand 50 one thousand due north o p q r s t u five west x y z aa ab Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998), Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Daily Life, Greenwood, ISBN978-0313294976

- ^ a b c Lambert, W. G. (2016). George, A. R.; Oshima, T. M. (eds.). Aboriginal Mesopotamian Religion and Mythology: Selected Essays. Orientalische Religionen in der Antike. Vol. fifteen. Tuebingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. p. 118. ISBN978-iii-16-153674-viii.

- ^ Stephens, Kathryn (2013), "An/Anu (god): Mesopotamian heaven-god, 1 of the supreme deities; known as An in Sumerian and Anu in Akkadian", Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, University of Pennsylvania Museum

- ^ a b c d due east f grand h i j k l m due north o p q r s t u v westward ten y z aa Blackness, Jeremy; Light-green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, The British Museum Printing, ISBN0-7141-1705-6

- ^ a b Wright, J. Edward (2000). The Early on History of Heaven. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN0-19-513009-10.

- ^ a b c d e f thou h i Choksi, M. (2014), "Ancient Mesopotamian Beliefs in the Afterlife", World History Encyclopedia

- ^ a b Barret, C. Due east. (2007). "Was grit their food and dirt their bread?: Grave goods, the Mesopotamian afterlife, and the liminal role of Inana/Ištar". Journal of Aboriginal Near Eastern Religions. Leiden, Holland: Brill. 7 (1): 7–65. doi:10.1163/156921207781375123. ISSN 1569-2116.

- ^ Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to life in aboriginal Mesopotamia . Facts on File. p. 143. ISBN978-0-8160-4346-0.

- ^ The Sources of the One-time Testament: A Guide to the Religious Thought of the Sometime Testament in Context. Continuum International Publishing Group. 18 May 2004. pp. 29–. ISBN978-0-567-08463-seven . Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ God in Translation: Deities in Cantankerous-cultural Discourse in the Biblical Globe. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. 2010. pp. 42–. ISBN978-0-8028-6433-eight . Retrieved vii May 2013.

- ^ a b Coleman, J. A.; Davidson, George (2015), The Dictionary of Mythology: An A-Z of Themes, Legends, and Heroes, London, England: Arcturus Publishing Limited, p. 108, ISBN978-1-78404-478-7

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983), "The Sumerian Deluge Myth: Reviewed and Revised", Anatolian Studies, British Found at Ankara, 33: 115–121, doi:10.2307/3642699, JSTOR 3642699

- ^ Schneider, Tammi J. (2011), An Introduction to Ancient Mesopotamian Faith, M Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdman'southward Publishing Company, ISBN978-0-8028-2959-7

- ^ Hallo, William W. (1996), "Review: Enki and the Theology of Eridu", Periodical of the American Oriental Order, vol. 116

- ^ Blackness, Jeremy A.; Cunningham, Graham; Robson, Eleanor (2006), The Literature of Ancient Sumer, Oxford Academy Press, ISBN978-0-19-929633-0

- ^ "An adab to Ninlil (Ninlil A)". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-20 .

- ^ a b c Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983), Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer, New York Urban center, New York: Harper&Row Publishers, ISBN0-06-090854-8

- ^ Harris, Rivkah (February 1991). "Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites". History of Religions. 30 (3): 261–278. doi:ten.1086/463228. JSTOR 1062957.

- ^ Vanstiphout, H. L. (1984). "Inanna/Ishtar as a Figure of Controversy". Struggles of Gods: Papers of the Groningen Piece of work Grouping for the Study of the History of Religions. Berlin: Mouton Publishers. 31: 225–228. ISBN90-279-3460-half dozen.

- ^ "A hymn to Utu (Utu B)". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-twenty .

- ^ "A balbale to Suen (Nanna A)". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-20 .

- ^ "A balbale to Nanna (Nanna B)". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2010-02-xx .

- ^ "Inana's descent to the nether world". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Oxford University. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ F. Wiggermann, Nammu [in] Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie vol ix, 1998, p. 135-140

- ^ Brisch, Nicole. "Anunna (Anunnaku, Anunnaki) (a group of gods)". Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses. University of Pennsylvania Museum. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ F. Wiggermann, The Staff of Ninsubura, JEOL 29

- ^ "Mesopotamia: the Sumerians". Washington State University. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2009-06-22 .

- ^ "Hurrian Mythology REF 1.ii". Christopher B. Siren. Retrieved 2009-06-23 .

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1972). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. (Rev. ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN0812210476.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1956). From the Tablets of Sumer. The Falcon'southward Fly Printing. ASIN B000S97EZ2.

External links [edit]

- Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, on Oracc

- Sumerian Hymns from Cuneiform Texts in the British Museum at Projection Gutenberg (Transcription of the book from 1908)

- The Ekur: Sumerian Reconstructionist Ceremonial Magick

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumerian_religion#:~:text=Sumerian%20religion%20was%20the%20religion,literate%20civilization%20of%20ancient%20Mesopotamia.

0 Response to "What Monotheistic Religion Was Introduced to Mesopotamia Around 600 B.c.e.?"

Post a Comment